SCROLL TO BOTTOM FOR REFLECTIONS

Below I have listed my first (eventually discarded) frameworks for inquiry, followed by the eventual focus topic and context for my work this week.

Context (first attempt):

The Laws of Physics underline the behaviour of all things in our universe. As animators attempting to create an impression of reality, it is important to understand the effects of these laws. Time, in particular, is generally understood as a fundamental quantity. This means that it is a quantifiable aspect of the world that cannot be expressed in terms of another aspect. Mass is similarly understood, and is intimately linked with time when considering objects in motion.

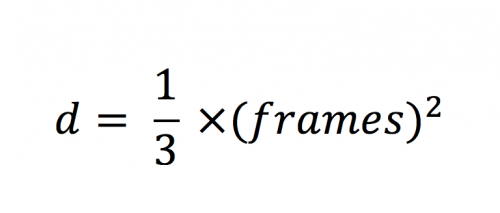

In Principles of Animation Physics, Alejandro Garcia proposes some rules for precise application of these laws on animation. When considering an object falling and accelerating under gravity, the distance fallen from the apex can be calculated using the following formula (Garcia 2012).

d = 1/3 x (frames)^2

**formula also attached as image**

He continues by elaborating that this calculation applies not only to a falling motion, but can be accurately scaled to jumping, walking, running, etc.

Even if we are not always carefully calculating the mathematic background to our animation, the relationship between timing and scale remains an important consideration. Larger objects with greater mass will appear to move slowly, whereas small objects with less mass or density will move, fall, or accelerate at a slower rate.

This is interesting to consider alongside factors such as viscosity, with specific regard to fluid animation. When varying only the timing of an action, does one’s interpretation of that material change?

The Pitch Drop experiment

Oil Drop

https://www.shutterstock.com/video/clip-28336789-closeup-liquid-oil-drop-laboratory-pipette-water

Water Drop

https://www.shutterstock.com/video/clip-1024293722-water-dropper-slow-motion-drop-falling-

Honey Drop

https://www.shutterstock.com/video/clip-1007775958-honey-flowing-spoon-against-black-background

https://www.shutterstock.com/video/clip-1009007396-honey-flowing-spoon-against-black-background

Method:

I will experiment with impressions of scale, mass and viscosity in animation by varying the timing of an action while keeping the animation itself as a controlled variable.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Now, find my secondary inquiry.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Context:

At the core of any media involving motion there is a passage of time. Making alterations to a character, environment, object or image over a series of still images creates the impression of movement and change when played back in sequence. But what about creating an impression of time in a single image, or frame? Audiences do bring a certain contextual understanding to an image based off their experience and are capable, for example, of extrapolating from a single frame how a man mid-walk would behave in the instances following that frame. However, how would one communicate movement in a still image to those without context for understanding the image? How might one create the impression of motion?

This has been heavily explored in a fine art and photographic context, and even as early as the Late Stone Age or Upper Paleolithic period in cave drawings from the Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave.

For Example:

Giacomo Balla - Dynamism Of A Dog On Leash (1912)

Marcel Duchamp - Nude Descending A Staircase (1912)

Harold Edgerton - Back Dive (1954)

Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave - Roughly 30,000 BC

Method:

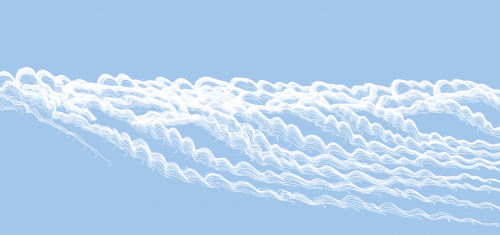

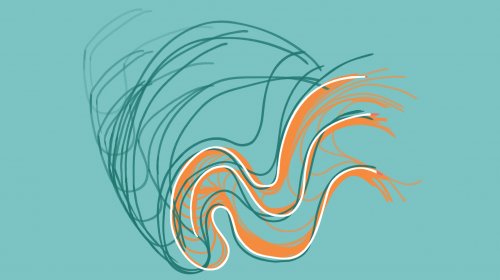

I will explore impressions of movement in a still image by creating animated sequences, then exporting only the Onion Skin output.

Response:

See images below

Reflections for Folio:

I found this exercise somewhat difficult to lock down. Before settling onto my final avenue of investigation, I was rather taken with the way time effects interpretations of scale and materiality in animation. I went about structuring this activity in a very scientific way, as fitting the calculated nature of the research I found for context.

However, as I began to execute the method I realized my initial thoughts were too focused on the application of time in animation and lacking in deeper consideration of the nature of time as material. I decided to dig further into uses of time in artistic renderings, and ways to communicate its passage in a still image. This was a valuable exercise, as it brought some greater context to my process overall by helping to situate my animation in a wider art context. Another important aspect of this exercise was building a deeper understanding of time as a tool in artistic works. My response was fundamentally no different to my usual output, though reflecting upon it has brought me a greater respect for that process, as well as other approaches to applying time innovatively.

This exercise stands starkly apart from my work in previous weeks, which has been trending towards immediacy and play as emerging ideas. My response here shares more similarities with my academic response to the Object-Oriented Ontology exercise, in that it was fundamentally a reflection on my practice, process and understandings of making.

Most importantly, this week taught me the worth of thinking about why a tool might be used rather than simply how. If I had continued with my first response to the theme, I wouldn’t have developed my creative workflow at all. Sure, it may have been an interesting experiment, but not nearly as insightful.

About This Work

By Evan McInnes

Email Evan McInnes

Published On: 22/05/2019