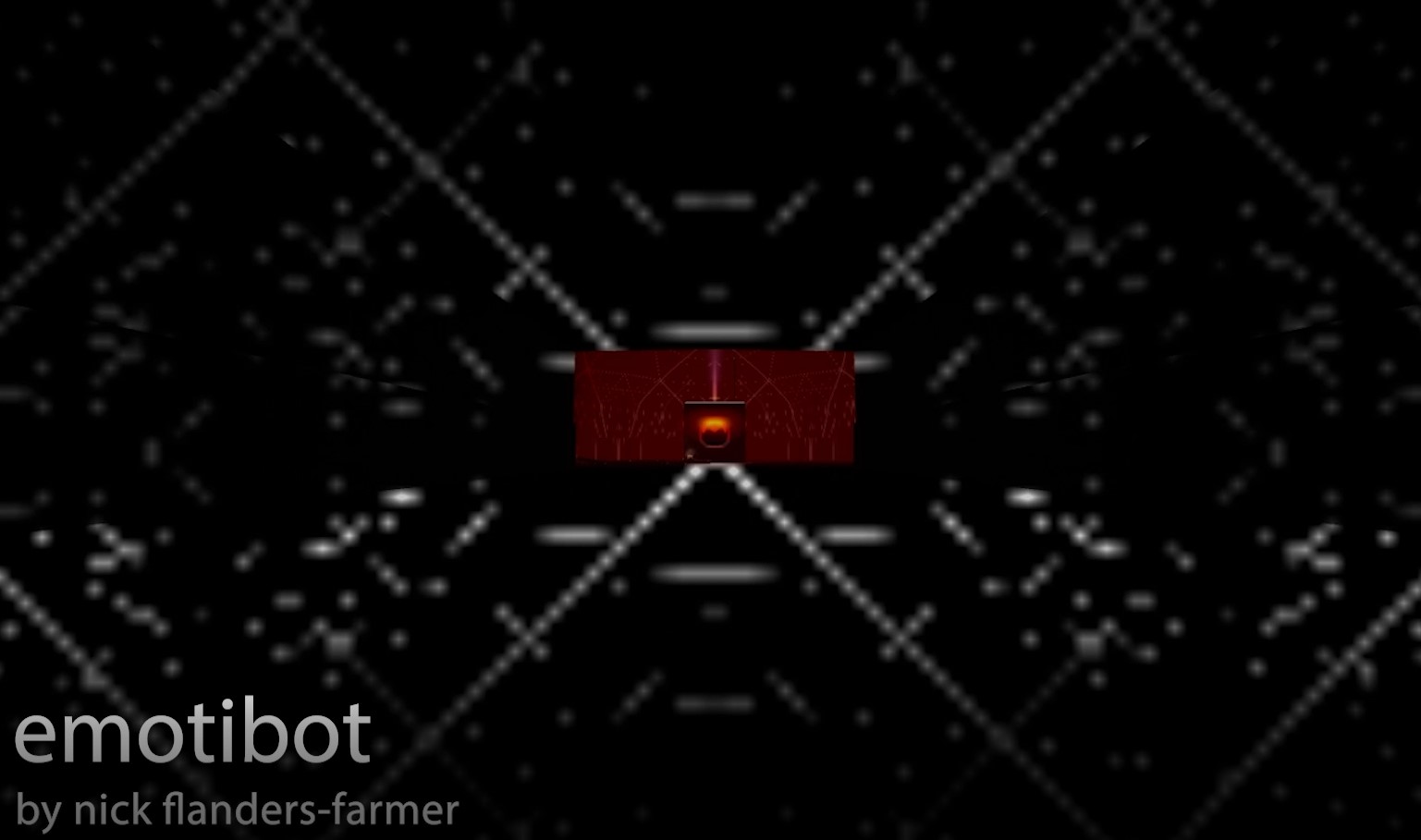

In response to the theme of Play and Abstraction, I created an interactive experience that explores the idea of abstracting abstract concepts. More specifically, the abstraction of emotion.

Context

My object this week, emotibot, is an interactive first-person experience. It borrows elements of its interactivity from games such as The Stanley Parable, in which in player can choose to follow the directions of the game’s narrator or reject them altogether.

Method

The goal of this piece was to take the concept of emotion and abstract it from its already abstract position. In my research, I found a quote that reinforced my initial theory, which I am regrettably unable to find now. The quote discussed abstract concepts like emotion and freedom, essentially saying that you can’t see freedom, or that you can’t hold freedom up to someone and have it be instantly recognisable. The fact that these concepts are universal yet difficult to represent reflects the innate humanity in them.

So, if a concept can’t be quantified, how can it be abstracted? The answer: by quantifying it.

I realised the only way to abstract emotion would be to manufacture it. The core of the experience is in the title itself, emotibot. emotibot is a digital brick, a gigantic supercomputer devoid of any humanity (aside from an old school digital voice). The player is free to roam emotibot’s immediate surroundings and will be addressed by emotibot depending on their location. If you stand to emotibot’s right it will praise you with love. Stand to his left and he’ll sink into a deep depression. Stop behind him and he will profess his untold rage.

These emotions aren’t real emotions, they’re regurgitated. Copied by an artificial intelligence that doesn’t understand them. To remove it further, they are an arbitrary collection of voice clips written by a university student attempting to make a point on abstract concepts. The removal of the human element makes the experience cold and uncomfortable, regardless of the words or sentiments being played over emotibot’s speakers.

The method for producing this piece was extremely simple, as the intention was to present a place devoid of recognisably human life. I modelled a simple room, modified a primitive cube to create emotibot, and used a handful of free starter assets from Unity to add various particle effects, sound, and a first-person character controller.

Response

emotibot is a cold depiction of an artificial intelligence, or some machine mimicking intelligence, attempting to display emotion towards a featureless protagonist. The relationship between the two characters could be described as tenuous, hostile, or even non-existent. As the player walks around emotibot they are scolded and revered by the inanimate block as it becomes apparent that the emotions it attempts to display are meaningless.

emotibot isn’t particularly playful; the act of experiencing it isn’t necessarily fun or game-like. However, its nature as an interactive piece invites interpretation and the ability to explore its world however you feel is appropriate. You are essentially in control of emotibot’s emotions and can repeat any which one as many times as you desire. You can explore the setting once, experiencing each emotion in sequence, and then leave. Play is exploratory here and extremely reflective. The act of experiencing emotibot forces the player to consider this computer’s ‘emotions’ and whether it actually has them.

Reflection

On a thematic level, emotibot is my most sophisticated interactive work yet. It reminds me of my archival object in Character, Place and Simulation, as both hold a certain ominous tone and are designed around first-person exploration.

The point I am trying to make is clear in the experience, and the packaging is unsettling. Even as the person who designed emotibot and wrote its dialogue I find myself at times feeling sympathy. It’s a strange feeling to have, to feel bad for a black digital brick in a video game I designed as it desperately asks for food and tells me how close to starving to death it is.

References

- The Stanley Parable, Galactic Café, 2011.

About This Work

By Nick Flanders-Farmer

Email Nick Flanders-Farmer

Published On: 28/10/2021