If the video link does not load. Gameplay footage of Momento is available at: https://youtu.be/THBkcHdvwGs

THEME: OBJECTS!

CONTEXT

In the lecture, I was intrigued by the idea of defining the object as a term. As someone who usually works with digital objects over tactile objects, my definition I came up with at the time was "A thing which is separate and whole". In addition to that, via some quick googling, were definitions from software designer forums, defining "objects" as "something which you can act upon and/or something that can act upon you", which comfortably includes people.

I was inspired by these blurry definitions, of the non-physical as an object, of groups as an object, and of parts as objects. My initial idea was to take something apart with friends and play around with what we felt were whole and separate things and how far we could push those definitions.(eg. What made an object distinctive? Shape, maybe, but what if theyre identical? What made multiple items a group? Proximity, maybe, but what if they're far apart?).

I was also inspired by the repetitive memory challenge in Helen Kwok's Looper Hand clapping game and the first chapter of Bryant's "Democracy of Objects".

METHOD

Come up with idea in Lecture

Find a material you van turn into a diverse range if objects, in this case I chose play-doh.

Refine idea and terminology through research.

Find playdough and dice and gather 1-5 friends.

Playtest until idea it's refined.

RESPONSE

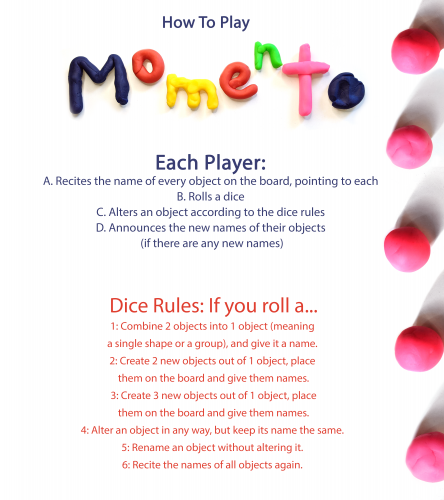

After several iterations, these are the rules to my game MOMENTO:

A. 2-5+ players sit in a circle, with a single die, and in the center are 3 blobs of playdough.

B. The player who set up the game names the 3 blobs of play-doh (eg. "Stephen", "Christmas Tree" and "The Magnificent Orb of Truth")

C. The next player then lists those names back, pointing to each object as they go.

D. That player then rolls a die, it lands from 1 to 6, and they follow one of the corresponding rules:

-

Turn two objects together into one. This can be a physical object or the theoretical object of a group (eg. "These two objects are dating and they form a new object called 'The Lovers'")

-

Turn Object into 2. Break it into 2 physical objects, shape, place and name those objects.

-

Turn one object into 3 objects. Break into 3 physical parts. Shape, place and name them.

-

Change the shape of an object but keep its name the same.

-

Rename an object without changing its shape

-

After reciting the names of all the objects at the start of this turn, recite them again.

E. The next player then points to and recites the names of every object on the table so far, rolls a die and repeats the cycle. This eventually creates more and more, smaller and smaller objects, memorizable by their shape, placement, relationship, group, history etc.

F. If a player can't remember an object's name, or says a name wrong, they are given a warning and on their second mistake they are eliminated. This carries on until there is one winner.

G. If somehow all objects recombine into 1, the player who combined them splits them back into 3 and gives them a fresh set of names.

Early on, to get a better sense of what I was doing, I read through the first chapter of Levi R. Bryant's "The Democracy of Objects", which is largely about justifying the lens which perceives objects under ontological realism, the idea that all things are of equal object-hood and can be perceived as having agency.

I did a couple of experiments inspired by this (having the player mold play doh with their eyes closed, having them drop every object and letting their objects shape determine its placement). Each idea was trying to give my play-doh objects agency in the game, and give the players less control over them, but they didn't exactly work out, and were more like obstacles players faced in trying to enjoy the game, than they were aspects of the game. But that said, if you really wanna get into the weeds of neo materialistic thinking, it could be argued that the agency of play-doh as a material is to be warped, changed, mixed and reshaped in exactly the way that the game allows. The game relies on play-dohs inherent properties, its character.

In the end, what I mainly took from the text was the theory surrounding "distinctions". A key point Bryant makes is about how, to draw a distinction, one must mentally eliminate what the object is distinct from. This is a key aspect of the game, because the player is constantly being asked to invent new distinctions and remember old ones.

The need to make distinctions in order to define and remember objects, had an interesting long term impact. All in all I played 10 rounds of the game with different people in different group sizes and once we had started playing, shapes and names never repeated. At 3 times, the playdoh was shaped into a penis for comedic effect, and even then they were unique from one another, even across multiple games. The same was true of names, once the name "Peter" was invented, used multiple times in one game, and eventually completely eliminated, 6 games later and there hadn't been another Peter. This I find particularly interesting because it would not have caused much if any confusion to repeat a name across games, but I think the intuition to only create "distinct" objects runs deeper than avoiding confusion. Once an object has been defined, used and removed, it has properties and a character and a history, and creating something new without referencing that history is rewriting over a solid object memory with a fluid one.

I was also inspired by Helen Kwok's "Looper Hand" memory game, which is very similar to a game I played as a child called "I went on vacation and in my suitcase, I put…" I love memory games in general, and I combined this with my love of making. The psychology of the proudly made object had a big impact on what objects got eliminated and which got kept.

Another thing I learned from the experience was the presence of rules in game-making, a topic I intend to research more into. My first iteration of the game did not have the dice rules, a player was allowed to do whatever they wanted, and while I thought that the players would naturally divide the dough into smaller pieces, they resisted making the game harder than it had to be. The rules were needed to keep the difficulty curve from staying the same and the game from just repeating itself. A game needs some challenge I realized. Whether I settled on the exact challenge needed to explore my original idea, I'm not sure. I worry that in creating 6 rigid rules, I'm missing something that can be done with objects distinctions that I didn't think of. I also worry that the medium of play dough may be limiting in some ways and I question how the game would play out if another medium was used.

There are several types of play I found in creating this game.

PLAY AS CREATION/ASSERTION OF IDENTITY:

-

Players love making things and hate destroying objects they put a lot of work into. (They are playing as an expression of both creativity and identity

-

Gameplay leans towards comedy, both as a self asserting social tool and a memorizing tool.

PLAY AS A QUEST TOWARD UNIQUENESS AND CREATIVITY:

-

Players unconsciously, I think, avoid repetition as much as possible. They lean towards uniqueness over all. (Which relates to play as a skill development tool, but also play as an act of creativity. I couldn't think of every method by which an object is defined while making the rules, but I'm confident, if the game were played long enough, the force of uniqueness would have us discover them all eventually.)

-

Surprisingly few players made objects that directly resembled their names / names that resembled their objects, perhaps because it felt uncreative. This happened despite the fact that players hated when objects they associated with their names were renamed or removed from play.

PLAY AS MENTAL AND PHYSICAL STIMULATION:

-

Players enjoy naming separate objects along a theme or scheme, so that their new objects have a relationship even if they aren't grouped into a single object (for example "These objects are Alvin, Simon and Theadore")

-

Players tend to begin struggling between 8 and 12 objects in but made it to 16-20 objects in the longest games.

About This Work

By Holland Kerr

Email Holland Kerr

Published On: 17/03/2021